If you could have a superpower, what would it be? Why?You can find more gems to rock the world, including What's the most extreme thing you've done in pursuit of reading or writing? and Describe your most defining experience with money, if you click here.

The ability to delete selected unpleasant memories. Which would be a whole can of worms because we're the products of all our experiences, good and bad. Lots of story potential there.

Friday, 28 December 2012

Litro

Monday, 24 December 2012

Sunday, 23 December 2012

Is it just me or...

Tuesday, 18 December 2012

New Sebastian Becker Story

It was late in the afternoon when one of the ward orderlies appeared in the doorway to Sebastian Becker’s basement office. Sebastian had spent most of the day clearing a space to work. They’d given him a desk and a chair, and a hook for his coat. He would have appreciated a window.

The orderly, clearly not expecting to find the room occupied, said, ‘Oh.’

‘Is that my welcome letter?’ Sebastian said, eyeing the envelope in the orderly’s hand.

‘That would depend, sir,’ the orderly said. ‘Are you the Visitor’s man?’The story continues here.

Sunday, 16 December 2012

On Being a Pro

To be carried along by that kind of inspiration is an exhilarating experience but, inevitably, there's a downside. The heart is not a great organiser. The evidence is there in all those would-be debut novelists who can't muster the craft to place a single short story with an indie magazine, but keep on sending out their 250,000 word epic.

Being a pro means being in control of your gift. The same's true whether we're talking about writing, art, dance, sports... anything. An outpouring of the heart can be high-value stuff but, like a kid in a kitchen, it needs a hell of a lot of cleanup to get anything presentable from it.

And when you're starting out, that's exactly what you do. You pour it all down onto the page, and then you look at it. You think it's wonderful. Others don't seem to get it. What will it take to make them see it the way you want them to? What do you have to change? What do you need to lose? What do you have to supply that isn't there already? Do it again. Do it different. Do it better. Make it work.

The balance starts to shift as you instinctively seek that magically right proportion of feeling and thinking. You learn to recognise what's right before you set it down, as opposed to having to work out what's wrong afterwards. If the balance shifts too far, if you become all calculation and no inspiration, then you fall into the habits of a hack. But mostly the process seems to take care of itself over time, as long as you keep at it.

I've lifted these thoughts from the afterword to the Telos Classics edition of Valley of Lights, in which I ramble muchly about the background to the writing of the novel and the circumstances surrounding its publication.

I may put more of it online in time, if I can work out how avoid dumping one big TLDR on you.

Saturday, 15 December 2012

From the Archive

The Stephen Laws archive, that is, or more correctly it's lifted from his Facebook page. No, it's not horror fiction's very own Boy Band. That's the late and much-loved Charles L Grant, me with Paul McCartney's hair, Laws, and Bigdog himself Joe R Lansdale at the BFS Awards.

Laws is a notorious pickpocket, which is why Charlie and I are guarding our change. Laws is venting his frustration by goosing Joe.

And what can I say? It was the 80s. We all tucked our shirts in our pants back then.

Wednesday, 12 December 2012

Dead Static

If you're in London, from now until Saturday night you can catch the second run of the science fiction comedy Dead Static at the Hen and Chickens theatre in Islington.

Tickets are nine quid. I believe there are still comps available for bona fide reviewers (ie, if you can prove you are one, and not that you just suddenly decided to be one to snag a freebie).

The List describes it as "Steve Jordan's science-fiction comedy about an over-confident smuggler and an insufferably upbeat conman trapped in a shuttle on a collision course with an asteroid belt." The play runs an hour and it's over a pub, so what's not to like? Have a drink, wander up to see the play, come back down and have another.

I saw it in its first run at the Camden Fringe. I had a great time. The show's associate producer is Little Miss Brooligan, aka Ellen Gallagher. Collar her after the show and ask her what an associate producer does and if you find out, tell me.

Logo design is by Paul Drummond, who designed this blog and the website of which it's part.

It's a tiny, tiny world.

Tuesday, 11 December 2012

Shedding Light on the Valley

Apparently some of the Amazon reviewers of my 1987 novel Valley of Lights contend that it owes something to Jack Sholder's movie The Hidden. In Valley of Lights, a Phoenix police sergeant is targeted by an ageless, amoral body-hopping entity that has been living on the fringes of society for so long that it can't even remember its own origin. It's not a great life; it's an eternity of lying low, until threatened by discovery.

Apparently some of the Amazon reviewers of my 1987 novel Valley of Lights contend that it owes something to Jack Sholder's movie The Hidden. In Valley of Lights, a Phoenix police sergeant is targeted by an ageless, amoral body-hopping entity that has been living on the fringes of society for so long that it can't even remember its own origin. It's not a great life; it's an eternity of lying low, until threatened by discovery.I wrote the book in '85 and in July '86 it was optioned by AWGO (Anciano Wyn-Griffith Orme), a newly-formed UK company with Hollywood feature ambitions. In October '86 director Stuart Orme went over and showed the script to New Line's Robert Shaye in the hope of getting New Line to back it. Shaye didn't say no right away. In '87 the book came out in hardcover, and in July the guys were confident enough to take me over to scout locations in Arizona and take some meetings in LA. I kept a diary of that trip which is included in the 'Telos Classic' edition of the novel. We interviewed casting directors as a step toward attaching a lead: Ed Harris was top of our wishlist, I recall, and William Hurt was on it as well.

New Line finally said no. The guys were talking to other backers as well, but when New Line released The Hidden in October '87 our movie was dead. We didn't know it right away, but it was.

Did The Hidden rip us off? It's hardly likely. But does Valley owe anything to The Hidden? Not a thing. It was out first.

Anne's blog post is here. I like The Hidden. It's a fun movie. I've never seen Fallen.

Thursday, 6 December 2012

It's Publication Day

Marilyn Stasio in The New York Times wrote:

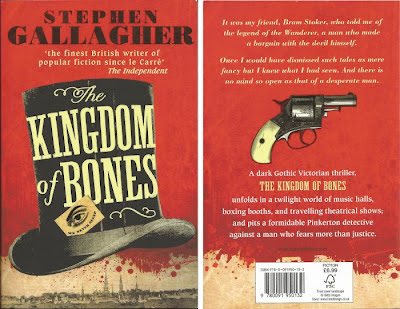

THE KINGDOM OF BONES... shows the occult mystery in its best light. Vividly set in England and America during the booming industrial era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this stylish thriller conjures a perfect demon to symbolize the age and its appetites, an entity that inhabits characters eager to barter their souls for fame and fortune. When met, this demon is residing in Edmund Whitlock, an actor whose life gives us entry into the colorful world of traveling theatricals. When Whitlock passes on his curse to the company soubrette, the troupe manager follows her to America, intent on rescuing her, and runs afoul of the law. Although Gallagher delivers horror with a grand melodramatic flourish, his storytelling skills are more subtly displayed in scenes of the provincial theaters, gentlemen’s sporting clubs and amusement parks where a now-vanished society once took its rough pleasures.And this from crime titan Ed Gorman:

"I read Stephen Gallagher for two reasons. First because he's one of the most entertaining writers I've ever read. And second because I can't read a short story of his let alone a novel without picking up a few pointers about writing. He's an elegant stylist, a shrewd psychologist and a powerful storyteller with enormous range and depth.

"I finished his latest novel The Kingdom of Bones and I was honestly stunned by what he'd done. The sweep, the majesty, the grit, the grue, the great grief (and the underpinning of gallows humor from time to time). This is not only the finest novel I've read this year but the finest novel I've read in the past two or three years."

Tuesday, 27 November 2012

Best of 2012

I believe a small glass of something may be called for.

The 'Read full review' link in the image won't work, but this one will.

While waiting for the softcover edition to be published in February, why not prepare the ground with Sebastian Becker's first outing in The Kingdom of Bones, in UK paperback from Ebury Press on December 6th?

No, you're quite right, I have no shame at all.

UPDATE: Click here to see all 100 titles in the Kirkus Best Fiction of 2012 list.

Saturday, 24 November 2012

Sherlocks

Here's the thing about American TV shows. Where British series can start out strongly and lose oomph as their overloaded creators run out of steam - witness the quality arc of Jonathan Creek, a Sherlock of the '90s - US series tend to find their feet as the team comes together. Much like the British Sherlock, the show's strength arises from a lead role played as a character part with all the stops out; though unlike the British version, Lucy Liu's Watson seems to be fading into the background with very little to do.

Comparisons are inevitable my sense is that Elementary's driven, dysfunctional take on a modern Sherlock owes more than a little to its British antecedent. Only a career-best performance from Jonny Lee Miller makes you rise above the thought that it's Benedict Cumberbatch's character with the serial numbers filed off. In fact you could pretty much swap the leads of the two versions, as Miller and Cumberbatch did nightly in the National Theatre's Frankenstein.

But the point was well made by a fan of both shows. With Sherlock, it's three a year. Fewer, if you average it out. Though it lost a couple of million viewers after the pilot, Elementary quickly got its 'back nine' pickup, extending the series order from thirteen episodes to a full season of twenty-two. CBS has since ordered a further two episodes to extend the season to twenty-four. It's a mass product for a mass market, and a successful one of its kind. And the more I see of it, the better it seems to get.

If we disdain something just because we think it's derivative, where will that leave us? Smug and pure, but with no popular culture and nothing to watch, that's where. You can have a preference, but it's still OK to see both. Life may be short, but it's not that short.

When I looked up Elementary's numbers, I was surprised to see how they compared to Eleventh Hour's in the same Thursday 10pm CBS slot. We got cancellation with a season's average of 12.15 million; Elementary's weekly average so far is 11.12 and they get a champagne party (as a continuing average that figure will reduce until the season's end, unless the lost 2 million from the pilot come back and rebalance it).

Here's the difference; Eleventh Hour was made for CBS by the Warner Bros studio. Elementary is made for CBS by CBS Studios. When the network pays its own studio for the show, the money stays in the family.

It's always about the numbers, but not necessarily about the numbers you think.

Wednesday, 14 November 2012

The Next Big Thing

It's called a Blog Hop. Here's how it works, he said to me. You answer ten questions on the next big thing that you're working on, then tag five other writers to do the same. Which sounds a little bit like that "grains of rice on a chessboard" thing... within a matter of weeks it'll all reach a crisis, and we'll be fighting each other over the last few taggable authors with rock axes and knives made from dinosaur bones.

What is the working title of your next book?

Well, the next one to appear will be the UK edition of The Kingdom of Bones but the one I'm working on is the third novel featuring Sebastian Becker, which I'm calling The Authentic William James.

Where did the idea come from?

I got my villain first. Which makes a kind of sense when you think about it. In this kind of story, it's someone's misdeed that sets everything in motion. If that's credible and there's genuine human motivation behind it, your foundation's going to be strong.

What genre best defines your book?

It's a big dark historical crime thriller, set in 1913.

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie?

Seriously, or in a fantasy-football-league sense? I'm not sure I can offer a thought for either. I'm not being evasive, but the career strategy issues and market politics of casting fascinate me. You don't often get the person you want. You get the most bankable person who needs your movie. If you're lucky, they'll connect with your vision to some extent; if they don't, you pretty much have to grin and suck it up. Having seen how it works, I find I can't do the speculation thing any more.

What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

A burning theatre, a kidnapped teen, and Sebastian Becker in pursuit of the morphine junkie cowboy that Buffalo Bill left behind.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

I'm represented. For the novels it's Howard Morhaim in New York, Abner Stein in London. For screen work I'm with UTA and The Agency. Please don't ask for an introduction. It doesn't work like that.

How long did it take you to write the first draft?

Ask me that when it's done. My first drafts are preceded by a lot of research and preparation. When I'm ready to sit down and pull it all together, it takes about twelve weeks.

What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

I'm sui generis, apparently. Which I suspect may be a euphemism for "difficult to place".

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

All the Becker books include an element of Old Showbusiness. In The Kingdom of Bones it was a touring Victorian theatrical troupe, in The Bedlam Detective there's a crucial element tied in with early British cinema. For decades after William Cody's final UK tour, a number of British fairground families made their living with home-grown Western sideshows. They lived the life and learned the skills of shooting, roping, knife-throwing... and in the original show, one of Cody's performers did suffer a horrific riding accident and stayed on in Europe to recover. My what-if question - what if one of the British families took him in to lend their act some authenticity? Only to find that they'd opened up their family to an embittered monster? Everything flowed from there.

What else about the book might pique the reader's interest?

It's the third novel to feature Sebastian Becker, Special Investigator to the Lord Chancellor's Visitor in Lunacy. He makes his first appearance in The Kingdom of Bones, published in the UK by Ebury Press in December. The Bedlam Detective follows in February.

These "Next Big Thing" blogposts are planned to appear every Wednesday. For next week, I'm tagging fellow Suspensers Joel Goldman and Harry Shannon, Cumbria-based crime writer Zoë Sharp, adopted son of Chicago Tim Lees, and Prince of Brit Horror Stephen Laws.

Kansas City-born Joel Goldman writes, "I became a ten-year overnight success with the publication of my first book, Motion To Kill, in 2002, introducing trial lawyer Lou Mason." Joel retired from his law practice in 2006 to write full-time, and has never looked back. His series include the Jack Davis thrillers and the soon-to-be-launched stories featuring Alex Stone, public defender.

Harry Shannon is a former actor, musician, Carolco VP, film music supervisor, now primarily a novelist with a sideline in short fiction. He's the author of the much-praised Mick Callahan novels. Media psychologist Callahan is "a failed Navy Seal, a recovering alcoholic and a loyal friend. He's also a man with a hot temper and a talent for getting himself into trouble."

Zoë Sharp is the creator of a series of novels featuring Charlotte 'Charlie' Fox, an action heroine who finds close protection work the perfect career for an ex-Special Forces trainee who has never been quite in step with life outside the army that rejected her. Zoë's hobbies are sailing, fast cars (and faster motorbikes), target shooting, travel, films, music, and reading just about anything she can get her hands on.

Tim Lees is a British author living in Chicago, responsible for numerous short stories and the pitch-perfect Frankenstein's Prescription, described as "a brilliant novel, one which takes the old stereotype and fills it with vibrant new life. The story is gripping, with each and every element of the plot fitting into place perfectly." (Peter Tennant, Black Static). It's available from Tartarus Press.

Newcastle-based Stephen Laws kicked off his career with Ghost Train. He's the author of 11 novels, numerous short stories (collected in The Midnight Man), as well as a columnist, reviewer, film-festival interviewer, pianist and recipient of numerous awards. He survived an early attempt by his publisher to promote him as "A Herbert for the 90s". Read about his heroic encounter with a Spanish zombie master here.

Sunday, 4 November 2012

The Killing 3

"I like working with the actors and with the producer, it's normal for me, but outside Danish Broadcasting, maybe it's old school – the director is king, the writer's more the guy you get some scripts from and then you see him again at the premiere. If they're just looking for a writer, then maybe I'm not the one."

Good interview with THE KILLING creator/showrunner Soren Sveistrup in The Independent - click here to read it in full.

Saturday, 20 October 2012

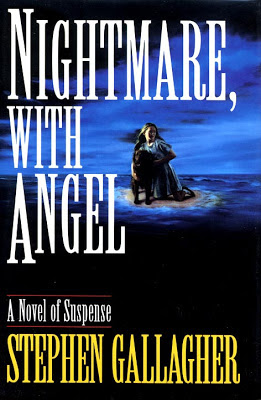

Nightmares and Angels

But in the most ambitious part of the trip, I headed East. Right across Germany, through the border, and into territory that had, only months before - weeks, even - been sealed off, self-contained, an enigma to the West.

For someone raised on spy fiction, this was no small deal. In Cold War mythology, East Germany was enemy territory. In reality the border was a zone of tension, and people died trying to cross it.

What I found was empty checkpoints, broken barriers, watchtowers with their windows stoned-in... there were concrete blocks that had been placed to prevent any vehicle from making a dash through, forcing the car into a zigzag path that no longer served any purpose. This once-fearsome locale now felt like a corner of an abandoned airfield, already becoming overgrown.

And what I found on the other side resembled the Britain of my earliest memories. It was as if time had stopped in the 1950s, which I suppose it pretty much had. Fields, farms, and villages were untouched. Where there was industry, it was like a concentrated dump of poison in an otherwise bucolic landscape. My most powerful visual memory is of the bright yellow hillsides of oilseed rape, unnatural in their intensity, a sight that always takes me back not only to the place, but to that precise time of the year.

I don't know what they must have made of the Volvo. At least half of the cars I saw on the road were Trabants, those tiny two-stroke polluters with bodyshells made of cotton waste and resin. The Volvo was a red 480 ES, one of those sports coupés with which they sometimes surprise the market, pictured here as it appeared in Bryan Talbot's The Tale of One Bad Rat. Driving around in it made me feel like Commander Straker in UFO.

I covered my checklist of sights and places, I gathered atmosphere and detail. It was all for a novel called Nightmare, with Angel.

I look back at some of the stuff I've done in the course of my career and wonder how I had the nerve. I had no one to guide me, I'd made no advance reservations. I didn't even speak any German. I did have a map and a phrasebook. I wasn't a complete idiot.

Here's how I began my pitch for the novel:

Imagine this.So the story that swept all the way to the East began closer to home, on a part of the British seacoast that I knew quite well. Sunderland Point is one of those places that can only be reached by a causeway at low tide. Strange, desolate and charming, it's one of the most atmospheric places I know. At the time I was experimenting with one of those panoramic cameras that took a picture like a school photo. It was a format that somehow suited the landscape.

You've got a nine year old girl who lives alone with her father in a big old house by the sea. Every day she looks more like her mother, and her mother was a tramp. Because of this her father all but ignores her, the woman who keeps house in the daytime also keeps her distance, and the child has to face a solitary life with only a scavenged photograph of her mother for comfort and a wishful image of what it might be like to be loved again. Her father isn't a hard man; but he's a mess, he's losing his grip, and he doesn't seem to see how he's losing his daughter as well. When he notices her, he's impossibly strict. But most of the time he's absorbed by his own bitterness, and he hardly notices her at all. Her days are long, and as bleak and empty as the coastal landscape around the house where she roams. With her father seemingly lost to her, she needs a father‑figure to take his place; and on the day that she falls into one of the big sea‑drains by the town dump and has to be rescued by a stranger, she thinks that she's found one.

His name is Ryan. He lives in a rented shack by the railway line and makes a living however he can; odd jobs, casual work, fixing up abandoned appliances, cleaning out aluminium cans and bagging them for scrap. He gets her out, he takes her home and, without waiting for thanks, he walks away.

But it isn't going to be so easy for him.

The novel did rather well for me, and one way or another it'll be available again soon. Don't ask me which way, because that isn't settled yet.

A couple of years later I traded in the Volvo for a sensible family wagon. Lots of legroom for the rear seats, plenty of luggage space, and room for the dogs.

This year, I traded back.

Monday, 15 October 2012

Creating the Audio Drama

It's only looking back that I realise how fortuitous my career timing was. With just one spec Saturday Night Theatre script it was like I stepped into radio's National Theatre. My very first producer (on Radio 4's The Humane Solution) was the legendary John Tydeman, who'd pretty much launched the careers of Joe Orton and Tom Stoppard. He was head of drama and led a very small team of highly experienced producers. Martin Jenkins did my next (An Alternative to Suicide) and I think with one exception he produced everything I wrote for BBC radio thereafter. We got on really well. While I was still working for Granada he came up to Manchester and I took him to see the outdoor set of Coronation Street, of which he was a fan. But he obviously enjoyed the fact that my stuff was anything but social realism, and that it gave him opportunities to push the medium in all kinds of unusual ways. On Alternative, which was a science fiction piece, I can remember the studio managers wiring up every piece of weird and extreme equipment in the building, tying up every channel and turntable. When I had to leave for my train they were still bringing in more.

On the half-hour Man in Blacks, I'd write the framing narration and it was understood that Martin would rewrite it for his needs. Those episodes now seem to be in constant repertory on Radio 4 Extra. Audio horror has an advantage, in that we're unsettled by incomplete information. Who's outside? What's making that noise? The moment you switch the lights on to see, that entire little universe of uncertainty collapses into something quantified. But with audio horror there's always something legitimately withheld.

I suppose if there's a weakness, it's that a lot of people imagine that an explicit visual trumps a quiet suggestion. If hearing someone scratching at your door is scary, the logic goes, then surely being confronted by them must be scarier still. I never really had to modify my writing because there was a very short note-giving chain and the people I was working with were all trained and experienced BBC staffers. But I can easily imagine having to deal with someone in the chain demanding that the uncanny be made explicit, because "that's what the audience will want."

As far as creating soundscapes is concerned, that's kind of interesting. Prior to my first BBC sale I'd written drama for a commercial radio station in Manchester. It was a music station but they'd made a commitment in their franchise application to deliver scripted content. We made the episodes as a kind of co-operative, in the sense of everyone mucking-in and no money. Tony Hawkins was their commercials producer, and he produced. Pete Baker was the breakfast DJ and he handled the technical side. Our cast was drawn from the actors and voiceover people we worked with every day (I was working in Granada's Presentation Department, just down the road). Pete devised a method by which we'd use our limited time with the actors to get a clean voice recording, and then he'd prepare all the sound effects on the instant-start cartridges used for commercials and jingles. Then he'd re-record the voice track through the DJ's desk in the station's unused backup studio, varying the acoustics with equalisation and playing in all the effects in real time.

It was a different situation at the BBC. There it was a rehearse-record system. Different parts of the studio were furnished in different ways to produce different kinds of sound quality, and effects were either created live with props by a studio manager, or played-in from pre-cued vinyl recordings on one of a bank of turntables. Watching it all come together was like some great elaborate ballet resulting in auditory magic. This was my words getting the historic BBC treatment and I was living the dream. But Pete's method was ahead of its time and gave a comparable result, I've always thought.

American radio drama was a quite different beast. When I imagine the kind of BBC drama I grew up with, I think of dignified thespians reading in a studio. But you listen to American 'old time radio' shows from the archives and they're like whirlwind rollercoaster rides with live music and a constant rain of shocks, stings, and climaxes. They're great fun but at the end of it you sometimes realise that it was all in the ride and nothing much of any weight has been said. The ideal is to try for something with a little more literary weight but still with that cinematic momentum.

I'd say that a good horror radio actor is one who'll go for the human truth in the scene where a lesser actor would fall into the trap of playing it for effect. Valentine Dyall – the original Man in Black, with whom I had the pleasure of working when I wrote for Doctor Who – let his natural gravitas do the job. Edward De Souza played it differently but just as effectively, by being sincere and not attempting to 'do creepy'. It's worth remembering that Vincent Price – another great radio voice – gave one of his career-best performances when, in Witchfinder General, he was shorn of all the tics and tricks that had carried him though many a crappy B-movie.

Sunday, 7 October 2012

Thy Kingdom's Coming

It is cool.

The cover is by Headdesign, who provided art for the current set of Ian Fleming's James Bond novels from Vintage. The back of the jacket features Sebastian Becker's Bulldog revolver.

As a bonus you get the opening chapters of The Bedlam Detective, the Becker-led follow-up. That one's scheduled for May 2013.

But this one's is available from December 6th. Just in time for... well, you know the drill.

Saturday, 6 October 2012

The Entitlement Thing

Editor Tom Spilsbury won't give any details, but did say that the reader is in his mid-40s. Now, I'm not saying there's anything wrong with a middle-aged man watching Doctor Who. It's a show for the kid in us all, and that's one of the reasons for its success. But anywhere past your teens and you're not the target audience, you're a guest. A welcome guest, for sure. But a guest needs to know how to behave.

There are aspects of the show that I think work well and others that rub me up the wrong way (coughRiverSongcough) but I wouldn't dream of getting exercised over them, nor of demanding that the show be retuned to my preferences. We can all have an opinion about what works and what doesn't but when it comes to what goes in, the young audience is the one that matters most.

I'll confess my unease at the recent BBC-backed convention that discouraged children from attending. It wasn't a cultural studies symposium, it was a fan convention. But an adults-only Who feels... wrong. Take the kids out of the equation, and it's like messing with the gravitational balance of the Whoniverse. To me the most joyous part about New Who is seeing adults and kids together, parents sharing and passing on their renewed sense of wonder, a cameraderie that crosses age barriers. Those adults who gather in pubs to discuss it amongst themselves are connecting over something that started inside them long ago.

If it's going down well with the kids in a way that doesn't suit some adults, that's a pity but it's not for us to hijack it, nor to pester the driver by clamouring for his personal attention. When the kids are turning away, that's when it becomes a serious matter for the showrunner to ponder. And it's bad enough having to deal with notes from executives, without viewers trying to get in on the act. When it comes to someone else's TV show I consider myself a consumer, not a stakeholder, and for very good reason. I don't seek to be given exactly what I want. I'm looking for discovery. The risk of disappointment is the necessary downside of wonder.

And disappointment seems to come very easily to many people, these days, with every new genre piece being released to the sound of sharpening knives. Our culture has become like a birthing pool full of crocodiles. There was a time when the response to new material was to invest in it, meet it halfway, go all the way to find something to love in it, should it happen to be a Plan 9 or a Robot Monster.

Now, like the twerp who logs in to Amazon and one-stars every piece of PC software because it won't run on his Mac, the default setting seems to be one of outrage that our specific expectations haven't been met.

And speaking as someone who spent a childhood lost in awe, oblivious to wires, zips, obvious model work, corny dialogue, and stories that didn't always make sense, I think we're the poorer for it.

Friday, 5 October 2012

Short Horror?

If you've made a suitable short film and you're willing to make it available, tweet me a link @brooligan or use the email form on my contact page.

I'll pass on anything you send. Unless it's naked pictures of your bits.

We have some standards, here.

UPDATE: Thanks to all who responded. I've passed along the links. She now has to contend with her ethics committee...

Monday, 24 September 2012

The LFS 'Running the Show' TV Drama Series Event

Speakers included Tony Garnett, Stephen Garrett of Kudos, and X-Files alumnus Frank Spotnitz whose new show, Hunted, is an international venture involving Kudos, the BBC, and HBO.

From the notes:

HUNTED – A new co-pro between BBC and HBO – there are two different cuts for broadcast on each (ie HBO has a lot more nudity!) It was written using a writers’ room, unusually for the UK. Series creator and showrunner Frank Spotnitz brought along his team of writers and explained how the process worked – he wrote the pilot solo, then met with his writers and they discussed where the characters & plot might go over the course of the series. Then they each took an episode and wrote it, with Frank rewriting all of them to varying degrees. It was a very collaborative process though. They treated the episodes like mini movies, deciding for each a particular movie that would serve as a ‘model’ for the tone and pace of the episode. During production, the writers were on set a lot, and also invited to be involved in the edit – they were involved at every stage.Other topics covered include ‘Trojan Horse’ drama, smuggling in originality while making a project seem like something familiar, and the high global demand for English-language drama. You can find the full piece here.

Writers Write. Don't They?

(I was going to say 'old comrades', but, you know, that would make her sound old, and she isn't.)

(Which I think should cover me if she reads this.)

I was aware of a couple of the jobs she'd done since we'd last met, but she'd had about half a dozen, skipping from one company to another for a variety of reasons... a departing boss, a vanishing drama budget, and in one case a writer-killer actor that no one wants to work with more than once. Entitled performers, take note. Similarly, she was aware of some of my recent credits but not the stories behind them.

I was telling her about the four US pilots that to date I've pitched, sold, and that haven't been picked up (the number's a bit of a cheat because I sold one spec script twice), and the new ideas I'm working on, when she said, "You're nothing like the other writers I meet."

"Oh?" I said, wondering what was coming next. "How so?"

"They don't bring in ideas."

"Then, what do they talk about?"

"They're looking to us to give them something to work on."

I should add that the company she's with is a serious player, and no, don't ask me to tell you which company it is.

This notion of writers without ideas of their own seemed alien to me, but apparently there's a whole raft of them out there and she gets a lot of them through her door. They're professionals, making a living. Some of them will take an assignment only to deliver late because they got another job elsewhere and worked on that instead.

Who are they? I have no idea. We don't move in the same circles and I can't even imagine their mindset. There's a notion I picked up from Mike Newell when we were developing one of my novels for a feature (unmade) - that the working life is divided between personal projects and 'gigs'. You bring the same professionalism to each but they mean different things to you. The quality of work stays the same. Often it's possible to blur the line between the two, if you can make some personal investment in a template you didn't invent.

The best gigs sustain and entertain you but the personal projects are always there, awaiting their chance. You keep a running Wish List. Some you fall out of love with, or they pass their sell-by date, but then every now and again a new one gets added to the list. I've learned that if the market doesn't want your stuff today, don't despair. If you sit on the bank of the river for long enough, the body of the latest BBC1 controller will float by.

I wondered if this (to my mind) passive attitude is an unintended consequence of British TV's diversion of new writers into its soaps and returning dramas. Once upon a time, if a writer shone in a soap or in fringe theatre, they'd get a shot at a single play on a subject of their choice. That's how we got Dennis Potter, Jack Rosenthal, Joe Orton, Alan Plater, Arthur Hopcraft, Stephen Poliakoff; and if they then went on to do series work it would forever have their distinctive and individual signature on it.

Those slots - Play for Today, ITV Playhouse, Armchair Theatre, The Wednesday Play, in retrospect the R&D division of British TV drama - no longer exist. A new writer today is most likely to be inducted into a world of long-term storylines and given episode structures. Which sounds to me like a bit of a honeytrap - you're offered a living but you give up your voice, like The Little Mermaid.

But I don't really know because I've never worked that way. I have worked in the American Writers' Room system, where a showrunner plus staff work together to give an authored consistency to twenty-two hours of television in a nine-month burst. But every one of those staffers has a spec pilot on their netbook and their eye on a showrunner's chair of their own. As did, in my experience, the writers' assistant, the showrunner's PA, and the script co-ordinator.

Have we bred the fire out of a generation of TV writers? On Said the Actress to the Vicar this blog comment from former Holby and Crossroads producer Yvonne Grace suggests that there's a happier medium in a reality of which I've no experience.

Whatever the case, the thought that there are gigs-only writers out there, looking to be hired but with nothing personal on their wish lists, came as a surprise to me.

Sunday, 5 August 2012

Fiction Reboot

A couple of weeks ago I answered a few interview questions from novelist/academic researcher/teacher Brandy Schillace, and the results are now online. I spouted stuff like:

A couple of weeks ago I answered a few interview questions from novelist/academic researcher/teacher Brandy Schillace, and the results are now online. I spouted stuff like:"Through my teens I read classic science fiction and ’60s British thriller writers. Then I had the advantage of a very solid three years of education in English Literature that opened up new avenues to me, from the medieval mindset to the poetry of Thomas Hardy. I think the point is that as a reader I had a big, big net, and a special fascination with popular fiction. I can remember buying Westerns and Romance novels, neither of which were of particular interest to me but I felt driven to find out what was going on in that kind of writing. I looked at William Goldman and Michael Crichton and saw that it was possible to be both a novelist and a screenwriter; Goldman kept the distinction clear and Crichton’s later, less substantial work showed what can happen when you don’t, so I learned from both of them."and

"Research is nothing more than expanded observation and as such, it’s key to all creation. Art’s about insight, and you can’t offer insight into nothing. Research is about continuing to write with authority after you’ve detected the limits of what you know."More dazzling autobiography and Secrets of the Universe here.

And while you're visiting, dig around a little. Dr Schillace's interest in the intersection of science, medicine and literature give her obsessions and researches an inevitably Gothic tint. Her published academic work covers areas of psychology, neurology, weird science and reproduction; here's a podcast recorded in the Wellcome Collection's club room, in which she discusses recent work on syphilis and Dracula, while if your imagination isn't piqued by her search across Europe for the Labour Device, an eighteenth-century "mechanical phantom used in the teaching of male midwives", then I don't know what would do it.

Thursday, 26 July 2012

CarNivorous

After that I steered wide of roadkill whenever I saw it coming, and as a result I suppose I became more aware of just how much of it there was. The road was like a suicide strip for small mammals. The desert was anything but deserted.

At the end of every day's driving, I'd have to clean off all the splattered bugs that had baked onto the windscreen. There were a lot of those, as well. Some of them had hit like bullets but most of them were just there, a silent accumulation like so much airborne plankton. They weren't just on the glass, they were all over the front end of the car.

It seemed like a shame.

And it felt like a waste.

Because that's when I started to think: wouldn't it be great if the car could make use of all that protein? I mean, it's out there and it's free and it dies anyway. Combustion engines have been around for barely more than a century, and already they've sucked half of the oil out of the planet. Living things have been around for hundreds of millions of years, and they just renew and get more numerous. Look at Birmingham.

I'm telling you, this is the way ahead.

It'll need some bright spark to come up with a functional design, of course. I picture it as some kind of a scoop at the front of the car and a big, flexible bag underneath, for digestion. It would have to be flexible because roadkill comes in all kinds of awkward sizes. Once it's in the bag, we could get really tricky and imagine it being broken down into endless complex molecules fuelling micro-engines throughout the vehicle's body. This would call for corrosive stomach juices made by designer enzymes, self-renewing, and some kind of a teflon lining to contain the process.

Or we could leave that for future generations of carnivorous cars and concentrate for now on getting heat out of the material. A TV documentary on Spontaneous Human Combustion showed that with one Coronation Street fan and a careless match you can generate intense heat energy over several hours, if the body's wearing surgical tights and a cardigan. Experimentation with our teflon lining should lead us to reproduce the 'cardigan effect' and before we knew it we'd have a road monster with real fire in its belly.

I'd give the scoop some maneuverability and the car a rudimentary predatory intelligence, so it could spot targets and react to them. I'd see this as a matter of simple humanity; a rabbit caught by the edge of the scoop and flung to the roadside is a life wasted. At the other end of the system, the exhaust pipe would be replaced by a rectum that would open and close like that gun barrel in the opening credits of the Bond movies. Waste products would probably be minimal and could be returned to the land, after the teeth had been sieved out.

All this is fine for places where the roadkill's thick on the ground, so to speak, but what about the UK?

Well, probably nothing much will change. While American cars are being fuelled by moose and coyote, we'll be puttering around in our little hedgehog-and-pigeon runabouts. But why restrict our thinking to roadkill? Apart from an obvious use for household scraps and leftovers, there are all those mad cow carcases and the entire European beef mountain to be used up. Not to mention hospital waste.

The petrol engine would be history. Who'd pay for expensive fuel when you could run down wildlife for free? But this is where the scenario starts to darken. Human nature being what it is, I can imagine plenty of people who'd think nothing of grabbing next door's cat when they thought no-one was looking, and stuffing it into the intake for some free mileage. Anyone out walking the dog had better be ready to dodge and run.

Then, as time moves on, hitch-hikers become fair game. Police speeding to the scene of any big road smash find passing motorists fighting over the bodies. Deceased relatives are fed to the family car with cries of, "It's what he would have wanted."

Meanwhile, those predatory instincts begin to evolve through successive generations of design. You keep 'em fed, or they turn on you. The wheel spins in your hand at the scent of a pedestrian. It's a race to make it safely out of the garage at the end of a journey.

Then late one night on a lonely road, you hear a rattle coming from the front of the car. It sounds expensive, so you stop to take a look. You crouch down in front to take a look. You find nothing... but it's already too late.

I'm telling you. It's a Mad Max future for us, whichever way we go.

First published in T3 Magazine

Monday, 18 June 2012

How Do I Get My Script Read?

"Any advice for getting a script read by some influential people?" A question asked of me recently that's impossible to answer in just a few words. But here's the digest version.

My experience is that "influence" is mostly a public illusion of power, and it's no subsitute for the actual ability to get stuff made, whether it's for film or TV. Those who can get stuff made are an ever-changing crowd, its composition determined by the ebb and flow of personal or corporate fortune.

Some of the players are obvious. Ridley Scott can get stuff made. Most companies riding high on a hit can get stuff made. For more names - you need to study credits, read the trades. And even Ridley Scott moves in a world where he's juggling with what's possible for him to achieve at any given time. I'm sure there are plenty of projects he'd love to be working on. But the ones he can get off the ground are those that the market wants from him right then. He'll have more choices than most, but you can be sure he doesn't operate by personal whim.

So, the good news and bad news. The good news is that the players are always on the lookout for new material to keep them in the game. The bad news - I call it bad news, actually it's just a fact of life - is that they get offered so much that each has to employ a fairly ruthless filtering system to cope with it.

But it's a filtering system, not an impervious wall. Bear in mind that it's designed to locate exactly the kind of thing the company's currently looking for - business research, not public service. Many companies. All different needs.

The first stage of the filter is usually an 'agented or solicited submissions only' policy. That's basically saying, "No cold callers". The expectation is that an agent will only submit material that's appropriate and of professional quality. Some agents shake that faith on a daily basis, I'm told.

A solicited submission is one for which the company has opened the door. A tiny percentage of these come through some privileged contact, giving mind-fuel to the paranoid. But once received, they'll go through the same Darwinian in-house procedure as all the rest, where nepotism or special access count for nothing. I've never seen a better insight into that process than the one given here by mega-producer Gavin Polone. He's writing about the industry in the US and you can scale it down a few notches for the UK, while bearing in mind that the number of outlets is proportionately smaller. (and if you scroll down the comments, it's fairly easy to distinguish the "Hollywood sucks" contributors from the professionally aware.)

You can get a solicited read for your script even if you don't have an agent. It comes down to this: give them a reason to be interested in you. Then they may have a reason to open the door, and to stand the expense of giving you serious consideration. Make your first mark. A short film, a home-made audio podcast, a bare-stage fringe two-hander with a couple of mates, a few short stories with a respected small press, a YouTube channel with a creditable following.

Something modest, achieved well, counts for more than something ambitious, achieved badly.

Then - enquire. The classic query letter. But draw your promise to their attention (and have the wit to research the company so that your material is a match for their needs, and your enquiry goes to the right person).

99% fail right there, which is a Good Thing because it thins the field for someone like you. More than three short paragraphs, and you've probably blown it. But if you come over as a sensible adult with a professional attitude, and your project is in their ballpark, you may be invited to submit. If not, don't attempt to turn it into a conversation. Move on. And meanwhile be planning your next short, your next fringe piece... maybe get on a Script Factory course, involve yourself in someone else's project. True creativity doesn't wait around for an outlet. Channel yours into growing that starter CV.

Every produced screenwriter that I know has followed some form of this path. Every one of them. You may hear tales of non-pros getting Hollywood breaks - I recall one about a taxi driver pitching a screenplay to his passenger in the course of a ride - but these are invariably more complex stories that have been shaped by some journalist into fairytale form.

Monday, 14 May 2012

The Silence of the Witness

I was told, "Don't be afraid to make it your own," and I've taken them at their word. It can be tricky, making a contribution to an established and long-running show; it's not your setup and they're not your characters, but you still have to bring your best game. Many of SW's writers seem to be regulars and it can be hard not to feel like some kind of an intruder.

One of the best things about the work has been the access to the top-level consultants and experts that the show has on standby, all of whom are alert to ways to enhance and advance the narrative. They don't just see it as their role to shoot down science flaws. Some viewers will recognise something of an Eleventh Hour vibe in my episode. Which will hardly be a coincidence.

So while we're at it, another shout-out for the people at Planet Hood, unshakeable in their drive to see a return of that show to US TV in some form. My stance all along has been supportive (well, obviously) while my energies have been directed, as they must be, into keeping up a working profile in a fast-moving business.

My feeling from the start has been that if Eleventh Hour should ever return, its optimum form would be that of CBS's one-off Jesse Stone TV movies. It's a form that could work rather well, I reckon, and it wouldn't be impossible to set up. I still have good relations with the Bruckheimer team - a couple of seasons ago we developed another show together, for a pilot that didn't get picked up. The next season I developed a non-Bruckheimer pilot for Fox while writing another for NBCU. I completed my coverage of the networks by working for ABC and this season I've a show that I'm pitching to cable. So if there's ever an opening for a rebooted version of a cancelled show, I'm in a position to chase it; what I can't do, alas, is force one.

But that's the game. As Lynda Obst wrote in her excellent Hollywood memoir Hello, He Lied, it's a business in which you have to ride the horse in the direction it's going. In other words, pursue what you want to achieve through the opportunities that you get.

Sunday, 22 April 2012

Dollhouse Thoughts

For me, Joss Whedon's Dollhouse was one of those disappointments that take a few episodes to fully sink in, as my Firefly buzz faded and it became all too clear that this broken show wasn't going to get any better. But in the DVD release (which I borrowed rather than bought) there's an extra feature in the form of Whedon's original uncut pilot, which sets up a very different show.

For me the big problem with the broadcast version was the idea of a heroine wiped clean for every new adventure - it sounds smart (Hey, she can be someone different every week) but in practice there's no character to engage with. There's a poetic angle to it (I'm reminded of Robert Stallman's Orphan trilogy, where the werewolf's alter-egos are decent people with hopes and dreams, unaware that their lives end the moment the beast's cover is blown), but you can't build a symphony on a grace note.

The original pilot addresses the true potential of the concept by setting up a show in which the heroine's personality has been imperfectly erased, and begins a secret struggle to survive and regain control in week-by-week increments. That was the show's real premise, overruled and ignored in the reshooting and recutting, only to emerge in the second season when cancellation was inevitable and Whedon, it would seem, was left to get on with it as he wanted.

I've heard it suggested that the way to get the most reward out of Dollhouse is to watch the unaired pilot and then skip straight to the second season. I haven't done it. But there ain't going to be no more Firefly, so maybe I will.

Wednesday, 4 April 2012

Bones and Bedlam

Although both Crown in New York and London's Ebury Press are part of the Random House group, the deals are unrelated.

Still feels like we're keeping it in the famiy, though.

Saturday, 31 March 2012

Stephen Laws

Tell him that I sent you. And that I'd labelled him 'odd stuff'.

Friday, 30 March 2012

#LitChat

You can follow the conversation using the #litchat hashtag, and join in by including the tag in your message or question. I'll be using Tweetchat to sort and filter the tweets. The moderator will be on the lookout for tweets without the hashtag, but even a safety net can sometimes be slipped through. Read more about the event here.

You don't need to follow me to participate. I'm on Twitter as @Brooligan, if you do care to follow, but don't expect to learn the secrets of the Universe. A selection of recent tweets appears below, by way of proof.

The LitChat will take place at 4pm EST, which I think equates to 9pm in the United Kingdom. Which I think makes it 1pm in California? Apparently different parts of the US put their summer clocks forward at different times, which results in a schism between EST and EDT to add to the usual East-West Coast differences. Chuck in last week's hour-forward of the UK's clocks and I'm amazed that life goes on, we all aren't at war, and planes don't fall out of the sky on a regular basis.

Thanks to Carolyn Burns Bass, #litchat founder and moderator, for the invitation.

Those Tweets:

Tried absinthe once. Next time just punch me in the face and blowtorch my tongue.

The Clarke Awards are for SF. The Dave Clark Award is for drumming more enthusiastically when you see your own closeup on the studio monitor

La-Z-Boy and Ladyboy. Sound very similar. Wonder how much trouble that must have caused over the years.

Karl Lagerfeld. To quote my grandma, what the f*** has he come as?

I'm singing along to a Bob Dylan track, and have to concede that he's way the more tuneful of the two of us.

"Doesn't suffer fools gladly" is code for "unpleasant asshole". Unpleasant assholes assume it's a compliment.

I sometimes look back and wonder if I'm the fool that others have suffered without letting me know.

"After viewing this item (The Bedlam Detective) customers buy Sherlock Series 2". WTF? Get back here. @steven_moffat says you smell.

Is it too late to organise an international manhunt for the bloke who told Christopher Lee he could sing?

Been asked to talk about the papers on local radio this Sunday morning. The D-lister rolodex must have come full circle again.

If you get a mommyjacker on Mumsnet, how do you tell?

Now that Terra Nova's been cancelled the field is again clear for my SPARTANS VS DINOSAURS (I'll do it one day. I will.)

Coughs and flu in the Brooligan house. Place has been rattling like the Bronte parsonage for the past week.

Used translation software to put on an article on Prof Challenger from German into English. THE LAND OF MIST came out as COUNTRY OF MUCK.

And finally, the perennial...

By the way, did I ever mention I had a book out..?

Wednesday, 29 February 2012

Stasio on Crime

"Gallagher’s detective is a man of fine character and strong principles, but he’s upstaged by the monsters he pursues. Watching Becker track down a pedophile is gratifying, but it can’t beat the sight of 20 overburdened boats hurtling through white-water rapids or Sir Owain, armed to the teeth and blasting away at giant serpents only he can see."The complete review here.

Tuesday, 28 February 2012

The Reprisalizer

Anyone familiar with British 70s paperback series, and particularly those from the New English Library, will know exactly what's going on here.

Anyone familiar with British 70s paperback series, and particularly those from the New English Library, will know exactly what's going on here. This spoof site is the brainchild of British comedy actor Matthew Holness, whose previous comic creation was horror writer Garth Marenghi, the "self-appointed mastermind author" and writer, producer and director of Garth Mareghi's Darkplace. Imagine if the UK's worst horror hack had been given the sets, cast, and budget of the cheapest 80s daytime soap, and you're probably there.

Holness's new creation is Bob Shuter, "suburban vigilante", riding a "red hot trail of vengeance through the urban hell of Thanet" in such titles as I, The Fury, Stock Car Slaughter, and Riot in Borstal Wing 'B', all supposedly the work of prolific and plainly demented wordsmith Terry Finch.

Apparently there's a Reprisalizer feature in development which plays a line between satire and dark psychology. It's expanded from Holness' 17-minute short A Gun for George.

Personally I'm torn between appreciation of the spoof, and feelings of genuine nostalgia.

Tuesday, 14 February 2012

The Kindness of Strangers

"Gallagher has been called a horror writer, a fantasy writer, a non-fantasy writer, a writer for big screens and smaller ones, a writer whose considerable talent has enabled him to slip in and out of genres precisely as if those tidy little boxes didn't exist - as indeed they don't for his character-driven books. In this one, Sebastian Becker (The Kingdom of Bones, 2007, etc.), his fast-track career abruptly derailed, contemplates an uncertain future...[snip]

...Gallagher loves character development but respects plotting enough to give it full measure. The result is that rare beast, a literary page-turner."

UPDATE: The full review is now online and you can read it here.

Sunday, 12 February 2012

Savage Season Interview

"I’ve never consciously scheduled my career to the extent that I could say, Oh, yeah, I put this aside and focused on that. If you do this for a living then you’re relentlessly pushing to do all you can all the time in whatever medium. And when you feel a bit of give, see a chink of light, sense the opportunity to get something off your wish list and out into the world, then you pour all of your energies into that."See me sort out the future of publishing, the impact of the eBook, selling your stuff to America, the role of the small press, and everything short of World Peace here.

(Actually, it's mostly "me, me, me")

And while we're at it, internet, there is no such thing as a "sneak peak".

Saturday, 11 February 2012

I got piles

With thanks to Stephanie.

You can order from B&N online here, where they're also selling the eBook for the Nook and taking pre-orders for the audio version.

Thursday, 26 January 2012

Murder Rooms: The Ultimate Collection

If you were planning to order this DVD set, hold off; there's a problem with it.

If you were planning to order this DVD set, hold off; there's a problem with it. Instead of the promised widescreen remastering, the discs contain stretched and distorted 'fullscreen' images of very poor quality.

Even at 4:3 the transfer is pretty awful. My set's going back, pronto.

I've emailed the distributor and I'll pass on whatever I find out.

UPDATE:

It's not looking good. The distributor seems to think that the quality's acceptable and calls it a 'multi-aspect ratio transfer' - which means that it's a 4:3 that'll distort itself to fit whatever TV screen you show it on.

Disappointing, perplexing... I have to say, don't touch it. It looks awful.

Sunday, 15 January 2012

The Movies, Mr Fairbanks, and Me

Looking back, 1977 was a key year for me. I didn't rocket to fame, I didn't take British culture by storm - though I'm sure those were the dreams I was having at the time. What I did in '77 was to stage a play with a local amateur company (a talented bunch who deserved better material, if I'm honest), sell my first radio drama, and see my first book in print (a novelisation of said radio piece).

Looking back, 1977 was a key year for me. I didn't rocket to fame, I didn't take British culture by storm - though I'm sure those were the dreams I was having at the time. What I did in '77 was to stage a play with a local amateur company (a talented bunch who deserved better material, if I'm honest), sell my first radio drama, and see my first book in print (a novelisation of said radio piece).With all that going on, I thought I was the bee's nuts. I imagined I could do anything. In retrospect I was no shooting star, and in retrospect I'm grateful for that. I was getting the thing I didn't know I wanted; grounding for a sustainable career based in diversity. I've seen writers of my generation have a hit and disappear, or spend the rest of their careers struggling to match it, or be stuck repeating themselves until death offers a release.

For me, a different pattern emerged. I'd have a great year, then a shit year, then I'd reinvent the wheel. It's as bumpy as the Indiana Jones ride at Disneyland, and fun in the same rough hazards-and-surprises kind of way.

In '77, I was going to write a musical. It was going to be about Doug Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, about the glory of silent cinema and the birth of superstardom, about the formation of United Artists and the end of an era with the coming of sound.

I know with the success of The Artist it's trendy to say so, but I've always loved silent film. From before the Thames Silents presentations, before Michael Bentine's Golden Silents on the BBC, all the way back at least to Bob Monkhouse's Mad Movies, intelligently presented from his own collection. The only Oscar I've ever held was Robert Youngson's, for The Days of Thrills and Laughter. Monkhouse was the real deal as a collector but I once had a modest collection of my own, starting in childhood with a 50' clip of Chaplin's Easy Street that came with a second-hand tinplate projector from Shawcross's of Eccles, local auction house and Aladdin's Cave.

As a teen I'd wash cars and blow my savings on Super 8 prints of the classics; my first and most-wanted was Metropolis, my most-watched were the Fairbanks costume spectaculars - Robin Hood, The Mark of Zorro, The Black Pirate - every one of them a veritable foundation document for a different action genre. The Blackhawk catalogue, Thunderbird Films, Perrys of Wimbledon, Derann of Dudley - these were the dealers of my dreams.

As a teen I'd wash cars and blow my savings on Super 8 prints of the classics; my first and most-wanted was Metropolis, my most-watched were the Fairbanks costume spectaculars - Robin Hood, The Mark of Zorro, The Black Pirate - every one of them a veritable foundation document for a different action genre. The Blackhawk catalogue, Thunderbird Films, Perrys of Wimbledon, Derann of Dudley - these were the dealers of my dreams.I had special affection for Blackhawk's The Thief of Bagdad, which I'd run with the accompanying piano improv soundtrack by Florence de Jong and Ena Baga. The music was recorded during a screening at the Academy One cinema, and issued on vinyl. I was going to add "issued on vinyl for geeks like me" but I was a dabbler, really, compared to some. I've an awful suspicion that my love for any subject is determined by the extent to which I can steal from it.

So in '77, heady with a droplet of success and firm in the delusion that I could tackle anything under the sun, I set my sights on Doug and Mary.

He was Hollywood's biggest male star, and she was "America's Sweetheart". Fairbanks was a graceful athlete of spontaneous creative instincts combined with great determination, while Pickford was as clearsighted in business as she was vulnerable onscreen. Their romance was genuine, their partnership golden, its ending a sad disengagement. There was a shape there; the key would be to find a theme.

In the late 70s Doug's only son, Douglas Fairbanks Jr, was living in London's Mayfair. It has to be tough following in the footsteps of such an iconic father but Douglas Jr had made his own mark, first with (in his words) "big roles in little pictures, and little roles in big pictures" and then, following distinguished war service, some big roles in big pictures and an active role in early international TV production. With all the confidence of an upstart, I wrote to him.

(By which I mean I wrote him a proper letter, not its modern, mass-emailed, hey-you-you're-famous-so-help-me-out equivalent.)

He wrote back, generously and at length, and more than once.

13th June, 1977.The hair rises slightly on the back of my neck as I read the reference to "my step-mother" - Mary Pickford was still living at the time, and stayed with us until the end of the decade.

Dear Mr Gallagher

Thank you very much for your courtesy in writing and I am proud and delighted that you would want to write something about my father’s career.However, I do want to warn you that the idea had already occurred to two or three other people over the past fifteen or twenty years, and even though they have been well-known playwrights and theatre people the projects have come to nothing because, except for a couple of domestic problems, my father's life per se was not sufficently dramatic to justify a play. His career was indeed spectacular and he was unquestionably a great creative artist and producer but beyond that the material is not rich enough to sustain a complete play. Any detailing of domestic sidelights would be likely to lead to complications as some of the people are still living - such as my step-mother.

I have no personal objection to your trying to write such a play but I thought it only fair to warn you that others had come to a dead end working on the same idea. There have been two recent books about my father which I would recommend to your attention: “DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS, THE FIRST CELEBRITY” and "THE FAIRBANKS ALBUM", both by Richard Schickel. These are both well researched and accurate and make interesting reading but I do think they would be difficult to dramatize. The most theatrical part of my father’s life was on the screen rather than off.

Yours sincerely

Douglas Fairbanks

As it happened I'd read the first of the Schickel books under its American title of His Picture in the Papers. I didn't keep copies of my own end of the correspondence, so I can't say what impression I was making. But I must have communicated at least some of my enthusiasm.

I mean, just look at this.

23rd June, 1977.Toward the end of the year Fairbanks went to Australia, touring his stage production of The Pleasure of His Company, but he took the trouble to have his assistant update me with his New York address for correspondence after the tour.

Dear Mr Gallagher,

I was most interested in your kind and informative reply to my letter and I will be most interested to follow your progress in your intended dramatization.

I must however invite your attention the fact that the "decline" of the careers of certain film artists after 1930 was due to a number of different reasons - unique to each individual - and not because of the problem of the market no longer providing the suitable outlet you refer to.

In the case of D. W. Griffith, for example, his own decline as a director began several years before that and had really nothing to do with either the advent of sound or the changes in corporate interests. It was merely that this very great talent had burnt itself out and his films, even in the middle 20s when he continued to have a free hand and satisfactory budgets, no longer enjoyed either public or critical support. The situation, despite everyone's goodwill, became too expensive and risky to go along with and no one appreciated this fact more than Griffith himself. Consequently the other partners of United Artists covered for him as best they could and he eventually retired from that association.

Keaton on the other hand was quite another "cup of tea” in so far as he had never really been completely his own master in terms of production and distribution. He was recognized within the profession as being one of the most gifted and original of all comedians but he was never too interested in business per se. Even when his silent films had begun to slump and he associated himself with Joseph Schenck (as a result of his marrying the sister of Norma Talmadge, who was then Mrs Schenck) in order that the burden of production would not fall on him, this did not work out. The introduction of sound films may have made some difference in the end, but it was not really the main problem, which was somewhat like that of Griffith in so far as the public no longer supported him in the way that they once had, and his prestige and drawing power- even at its height - could not compete with Chaplin's. It is only now in retrospect that we realize that he was actually in many ways Chaplin's equal as a mime, but it was not as fully appreciated then as it is now.

The case of my father and Chaplin was something else again. It was not that their careers "declined" because of the need to "reshape their careers" nor to the introduction of corporate interests entering the field. It was largely due to the fact that both Chaplin and my father had believed that their best medium was the purely pictorial or visual form of story-telling and that they did not really want to introduce or participate in sound films themselves. When they did so it was due almost entirely to their obligations to the company they had formed together, and they took relatively little interest and had little enthusiasm for what they did so long as they were meeting their responsibilities as partners. They had no objection to sound films made by others, and in fact enjoyed them immensely, but they did not really want to even try for themselves. Both Chaplin and my father had hoped to avoid the responsibility of making more films unless they were silent but could not do so and had to alter the original concept of United Artists and bring in others who would supply enough production to maintain the overhead costs of their distribution organizations. It was less them but more my stepmother, Mary Pickford, who actually went out and sought others to join United Artists - such as Joseph Schenck (mentioned above), who also later brought in Daryll Zanuck and later Samuel Goldwyn. But the short answer is that they were all professionally "tired" and preferred to let the original United Artists concept be altered, and hence gradually pulled out of production altogether. There was no real drive or wish to continue their careers as such because in fact they had none of them suffered any very severe reverses. They just lost interest and evolved a plan to expand their corporation so that they could "slide out" of their obligations and let others "carry the ball". Miss Pickford was the only one who really wanted to continue and so the various changes that took place over the next ten or more years at United Artists were usually opposed by her and she was the last one to sell out her shares. I know very well that my father could have - had he wanted to - continued to produce films of the same quality and of the same standard as before, but he quite openly admitted that he no longer had any desire or wish to.

The proof of my statement lies in the way he practically "cheated" in the making of his last few films. "Round the World in 80 Minutes" came about only as a result of putting together his films of a world tour he made - originally intended for a private record and later, when he realized that he must deliver something, he added some linking sequences on his return and put it out as if it had been planned that way from the first. Mr. Robinson Crusoe was never “planned” but came about as a result of a yachting cruise he made with some companions in the Pacific and, when they arrived in Tahiti and again he faced pressures from his partners and the distribution organization repeated its demands, he decided to use the cruise as the basis for a film. It was made in a relatively haphazard way and as a result of a snap decision to do something. Once again, additional scenes were made later upon his return and he was glad to be done with it. “Reaching for the Moon" and "Don Juan" commanded so little interest and enthusiasm from him and he was so wrapped up with other matters in his private life that he, for the first time since his first year in films, delegated practically all of the responsibility for production to others, managing thereby to divest himself of the chores he once enjoyed and to honour the agreement with his partners with the least trouble to himself.

In other words, what I am trying to suggest is that in these latter cases it was not that their careers declined for the reasons you suggest but because they had run out of ideas, used up their energies and really did not wish to adapt themselves to changes in the medium. They were delighted when new partners were brought in and they could sit back and let others carry the load that they had originally carried.

I trust the above will be of some interest and use to you as it is in fact a matter of record as to what happened.

The last letter I have came from the Town House in Adelaide in the November of that year. I'd been telling him of some of the material that his advice had led me to, and he wrote:

I was most interested to read of the progress you have made wading through all that very dated and often unreliable material... X’s book is, as you suggest, a very good one in many ways and indeed it is one of the best although even here I have found numerous errors, some trivial and some serious. It is so awfully hard to be certain about anything concerned with such a self-disguising industry as the Motion Picture Industry.It pretty much ended there because he'd been right from the beginning; despite my fascination with the subject, in the end I couldn't crack it.

With the best of wishes.

I am,

Sincerely,

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS JNR.

But what a gentleman. I can only hope I showed an adequate appreciation of his kindness.